Ole Anderson

Ole Anderson

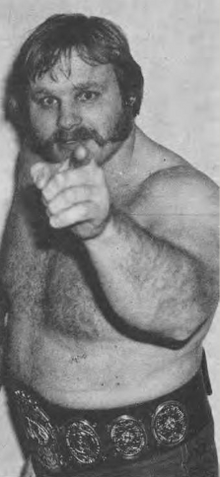

| Ole Anderson | |

|---|---|

Anderson, c. 1982

|

|

| Birth name | Alan Robert Rogowski |

| Born | September 22, 1942 Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | February 26, 2024 (aged 81) Monroe, Georgia, U.S. |

| Partner | Marsha Cain[1] |

| Children | 7, including Bryant[1] |

| Professional wrestling career | |

| Ring name(s) | Al Rogowski[2] Ole Anderson[2] Rock Rogowski[2] |

| Billed height | 6 ft 1 in (185 cm)[2][3] |

| Billed weight | 255 lb (116 kg)[2] |

| Trained by | Dick the Bruiser[2] Verne Gagne[2] |

| Debut | August 19, 1967[2] |

| Retired | April 28, 1990[2] |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Rank | |

Alan Robert Rogowski (September 22, 1942 – February 26, 2024), better known by the ring name Ole Anderson (/ˈoʊlɪ/), was an American professional wrestler, booker, and promoter.

Following a stint in the U.S. Army, Rogowski made his professional wrestling debut in his native Minnesota in 1967, wrestling for the American Wrestling Association (AWA) as Al “the Rock” Rogowski or simply Rock Rogowski. The following year, he debuted in the Carolinas-based Jim Crockett Promotions, where he adopted the ring name Ole Anderson and began teaming with his “brother” Gene Anderson as the Minnesota Wrecking Crew. Following a further stint with the AWA and appearances with Championship Wrestling from Florida, in 1972 Anderson settled into wrestling primarily for Jim Crockett Promotions and Georgia Championship Wrestling. By the mid-1980s, Anderson was a part-owner of, and the booker for, Georgia Championship Wrestling. After Georgia Championship Wrestling was acquired by Vince McMahon in 1984 in what was known as “Black Saturday“, Anderson broke away to form his own promotion, Championship Wrestling from Georgia, which was itself acquired by Jim Crockett Promotions the following year. Anderson spent the rest of his career with Jim Crockett Promotions and its successor, World Championship Wrestling (WCW), forming a new iteration of the Minnesota Wrecking Crew with Arn Anderson, co-founding influential stable The Four Horsemen, twice serving as booker for WCW, and running the WCW Power Plant. He retired from the ring in 1990, and from the professional wrestling industry in 1994.

Known amongst his contemporaries for his gruff, cantankerous demeanor and toughness, Anderson is a key figure in the history of professional wrestling in Georgia and the Carolinas. He held over 40 championships over the course of his career, including eight reigns as National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) World Tag Team Champion (Mid-Atlantic version). He was inducted into the WCW Hall of Fame in 1994 and the NWA Hall of Fame in 2010.

Early life[edit | edit source]

Rogowski was born to the Polish immigrants Robert Joseph Rogowski and Georgiana Bryant in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1942. He attended Alexander Ramsey High School in nearby Roseville, Minnesota.[4][5][6][7][8] He spent his adolescence in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he worked at his father’s bar.[6] As a youth he took part in amateur wrestling and football.[6][9][8] After high school, Rogowski attended the University of Colorado (where he played football for the Colorado Buffaloes), the University of Minnesota, and St. Cloud State University, but did not graduate.[6]

Rogowski served in the U.S. Army for three years,[1][6] reaching the rank of specialist.[9] During his service, he spent time stationed in Germany and performed clerical work.[10] While in the Army, Rogowski trained in amateur wrestling, boxing and powerlifting.[6]

Professional wrestling career[edit | edit source]

American Wrestling Association (1967–1968)[edit | edit source]

While exercising at a YMCA gym, Rogowski was approached by professional wrestler Tiger Malloy to meet with Verne Gagne, the promoter of the Minneapolis, Minnesota-based American Wrestling Association (AWA).[6][11] Rogowski was trained to wrestle by Gagne and Dick the Bruiser. He debuted with the AWA on August 19, 1967, defeating José Quintero in a bout in the Minneapolis Auditorium.[2][12][13] He wrestled as “Al ‘the Rock’ Rogowski” or simply “Rock Rogowski”.[2][14] He was occasionally billed as being the nephew of Dick the Bruiser, and as a relative of The Crusher.[6][15] He went on a short unbeaten streak which ended the following month when he and Mighty Igor Vodik unsuccessfully challenged Harley Race and Larry Hennig for the AWA World Tag Team Championship. In October 1967, Rogowski defeated Bob Orton for the AWA Midwest Heavyweight Championship; Orton regained the title from him the following month.[16] In December 1967, he twice again challenged for the AWA World Tag Team Championship, teaming with Bill Watts in a pair of losses to champions Dr. Moto and Mitsu Arakawa. Rogowski wrestled regularly for the AWA until June 1968, when he moved to Jim Crockett Promotions.[12] By the end of his first year in professional wrestling, Rogowski was earning $32,000 (equivalent to $280,000 in 2023) per annum.[5]

Jim Crockett Promotions (1968–1970)[edit | edit source]

In mid-1968, Anderson began wrestling for the Carolinas-based Jim Crockett Promotions. Adopting the ring name Ole Anderson (Ole being a traditional Norwegian Minnesotan name, and also a play-on-words referring to the toxic shrub oleander), he was presented as the “baby brother” of Gene Anderson and Lars Anderson from the Minnesota Northwoods. Billed as the “Minnesota Wrecking Crew“, the trio wrestled in a series of six-man tag team matches. In September 1968, they began feuding with Art Thomas, George Becker, and Johnny Weaver, culminating in a Texas death match in October 1968 that was won by Becker, Thomas, and Weaver. Following the Texas death match, Lars Anderson left the territory, and the Minnesota Wrecking Crew continued as a tag team.[4][5][17][18][19]

In January 1969, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew defeated Becker and Weaver to win the NWA Southern Tag Team Championship (Mid-Atlantic version); they lost the titles back to Becker and Weaver one week later. In January 1969, they began a long-running series of matches against the Flying Scotts. In June 1969, Ole and Gene were rejoined by Lars Anderson. The Minnesota Wrecking Crew resumed their feud with Thomas, Becker, and Weaver, and also began a series of violent matches against Aldo Bogni, Bronko Lubich, and George Harris.[18] After Lars departed once again in July 1969, Ole and Gene reverted to being a tag team.[18] In January 1970, Anderson wrestled a handful of matches in Japan with the Japan Wrestling Association as part of its “New Year Champion Series”, including losing to Antonio Inoki in Himeji.[20] In March 1970, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew defeated Becker and Weaver to win the NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Championship. They held the titles for 180 days (with successful title defences against teams including the Flying Scotts, the Infernos, and Mr. Wrestling and Tiny Anderson) before finally losing them to Nelson Royal and Paul Jones in September 1970. Anderson departed Jim Crockett Promotions later that month.[18]

American Wrestling Association (1970–1971)[edit | edit source]

In November 1970, Anderson returned to the American Wrestling Association, readopting his “Rock Rogowski” ring name.[12] Upon his return, he defeated Tex McKenzie to win the AWA Midwest Heavyweight Championship for a second time, losing the title to Stan Pulaski the following month.[16] Also in November 1970, Anderson challenged his trainer Verne Gagne for the AWA World Heavyweight Championship, wrestling him to a double countout.[12] In early-1971, Anderson held the AWA Midwest Tag Team Championship on two occasions, once with The Claw and once with Ox Baker.[3][21] Anderson left the AWA once more in mid-1971 to join Championship Wrestling from Florida.[12]

Championship Wrestling from Florida (1971–1972)[edit | edit source]

In July 1971, Anderson began wrestling for the Florida-based Championship Wrestling from Florida promotion. Shortly after arriving, he formed a tag team with Ronnie Garvin, with the duo winning the vacant NWA Florida Tag Team Championship later that month. They lost the titles to the Australians (Larry O’Dea and Ron Miller) the following month.[22] In December 1971, Anderson defeated Jack Brisco to win the NWA Florida Television Championship. His reign ended one week later when he lost to Bob Roop.[3][23] Anderson wrestled regularly for Championship Wrestling from Florida until spring 1972, when he left to return to Jim Crockett Promotions.[24]

Jim Crockett Promotions; Georgia Championship Wrestling (1972–1984)[edit | edit source]

Anderson returned to Jim Crockett Promotions in February 1972, resuming teaming with Gene Anderson as the Minnesota Wrecking Crew. Over the following months, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew faced teams such as Rip Hawk and Swede Hanson, the Von Steigers, Klondike Bill and Nelson Royal, and Ronnie Garvin and Thunderbolt Patterson.[18] In November 1972, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew briefly won the NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Championship for a second time by defeating Art Neilson and Johnny Weaver; Neilson and Weaver regained the titles one week later. In March 1973, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew defeated Neilson and Weaver to win the NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Championship for a third time.[25] In May 1973, Anderson won the NWA Eastern Heavyweight Championship from Jerry Brisco. He lost the title back to Brisco in July 1973.[26][27] The Minnesota Wrecking Crew’s third reign as NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Champions ended that same month when they lost to Jerry Brisco and Thunderbolt Patterson. They defeated Brisco and Patterson to win the NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Championship for a fourth time in July 1973; this reign lasted until October 1973, when they lost to Nelson Royal and Sandy Scott.[25]

In October and November 1973, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew toured Japan with International Wrestling Enterprise as part of its Big Winter Series, facing tag teams such as Isamu Teranishi and Strong Kobayashi and Animal Hamaguchi and Mighty Inoue. They unsuccessfully challenged Great Kusatsu and Rusher Kimura for the IWA World Tag Team Championship in a two out of three falls match. The tour also saw Ole Anderson face Rusher Kimura in a pair of cage matches. The final match of the tour, which took place in the Korakuen Hall in Tokyo, saw the Minnesota Wrecking Crew and Klondike Bill lose to Great Kusatsu, Mighty Inoue, and Rusher Kimura in a six-man tag team match.[28]

In May 1974, Anderson began wrestling regularly for Georgia Championship Wrestling. From 1974 to 1985, Anderson wrestled primarily for Jim Crockett Promotions and Georgia Championship Wrestling.[17]

In October 1974, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew defeated Bill Dromo and Mike McCord for the NWA Southeastern Tag Team Championship (Georgia version) in Columbus, Georgia. They lost the titles to Buddy Colt and Roger Kirby the following month.[29]

In January 1975, Ric Flair was introduced to Jim Crockett Promotions as a cousin of Ole and Gene Anderson, with the trio taking part in a series of six-man tag team matches.[7][30]

In 1975, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew faced Paul Jones and Wahoo McDaniel in a series of matches for the NWA World Tag Team Championship. A June 1975 match featured the “supreme sacrifice” angle, which saw Ole ram McDaniel into Gene’s head, knocking both men out and enabling Ole to pin McDaniel.[4]

In May 1976, Anderson was attacked by a knife-wielding audience member in Greenville, South Carolina. The attacker slashed his arm and chest, necessitating the reattachment of tendons and a large number of stitches.[6][4]

In 1976, Anderson was appointed as booker of Georgia Championship Wrestling by majority owner Jim Barnett, replacing Harley Race.[31][32] Anderson eventually became a part-owner of Georgia Championship Wrestling.[6] He also had a stint booking JCP in 1981–82. For a time he even booked both companies simultaneously, often combining both rosters for supercards which were noted for offering some of the best action in the business at that time. He later left JCP to book and wrestle for GCW full-time.[citation needed]

By 1977, Anderson was earning $140,000 (equivalent to $704,000 in 2023) per year.[5]

In May 1977, Anderson defeated Mr. Wrestling II in Macon, Georgia to win the Macon Heavyweight Championship. He held the title until January 1978, when he lost to Dick Slater.[33] In December 1977, Anderson and Jacques Goulet defeated Tommy Rich and Tony Atlas for the NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship; they lost the titles to Atlas and Mr. Wrestling II in February 1978.[34] That same month, Anderson defeated Goulet in the finals of a tournament in Atlanta, Georgia to win the NWA Georgia Television Championship; he lost the title to Thunderbolt Patterson in May 1978.[35]

In mid-1978, Anderson formed a tag team with Ivan Koloff. In June 1978, the duo defeated Thunderbolt Patterson and Tommy Rich for the NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship. They held the titles until September 1978, when they lost to Rich and Rick Martel. In October 1978, Anderson teamed with Stan Hansen to win the NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship for an eleventh time; Anderson and Hanson were stripped of the titles the following month after being disqualified too many times.[36][34] In November 1978, Anderson defeated Mr. Wrestling in Columbus, Georgia to win the Columbus Heavyweight Championship. He was stripped of the title the following month after a match against Bob Armstrong.[37] In early 1979, Anderson won the NWA Georgia Television Championship from Thunderbolt Patterson; he held the title until April 1979, when he lost to Bob Armstrong.[35] In January 1979, Anderson and Koloff defeated Jack Brisco and Jerry Brisco to win the NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship, losing the titles to Norvell Austin and Rufus R. Jones in April 1979. Anderson and Koloff won the titles once more in June 1979, defeating Tommy Rich and Wahoo McDaniel; this reign ended in July 1979 when they lost to Rich and Hansen. Anderson and Koloff defeated Rich and Hansen to win the titles a fourth and final time in August 1979, losing them to Rich and Crusher Lisowski the following month. Anderson and Koloff stopped teaming regularly in September 1979.[36][34]

In October 1979, Anderson teamed with Ernie Ladd to defeat Crusher Lisowski and Tommy Rich for the NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship. After a handful of title defenses, the team fell apart later that month when Anderson turned face, and Anderson began feuding with Ladd. In November 1979, Anderson and Stan Hansen faced Ladd and Masked Superstar to determine who would be the NWA Georgia Tag Team Champions; after the match ended in a draw, the titles were declared vacant. In December 1979, Ladd defeated Anderson in a Texas death match.[26][34][38]

In July 1980, Anderson was involved in one of Georgia Championship Wrestling’s more infamous angles. After turning face, Anderson had repeatedly petitioned his former rival Dusty Rhodes to team with him. Rhodes eventually acquiesced, and the duo challenged the Assassins for the NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship in a steel cage match in the Omni Coliseum, with Gene Anderson and Ivan Koloff as guest referees. During the match, when Rhodes attempted to tag Anderson in, Anderson instead attacked Rhodes, leading to all five heels beating down Rhodes. Following the attack, Ole Anderson gave an interview to Gordon Solie in which he gloated that he had planned the betrayal for over a year.[26][39]

In February 1982, Anderson and Stan Hansen won a one night tag team tournament, defeating the Blond Bombers in the final. The duo subsequently formed a tag team that competed in both Georgia Championship Wrestling and Jim Crockett Promotions. Later that month, Anderson and Hansen defeated the Brisco Brothers (Jack Brisco and Jerry Brisco) to win the vacant NWA World Tag Team Championship (Mid-Atlantic version). Over the following months, Anderson and Hansen successfully defended the titles against challengers including Dusty Rhodes and Ray Stevens; Don Muraco and Wahoo McDaniel; Ivan Putski and Tom Prichard; and the Fabulous Freebirds.[40] Anderson and Hansen vacated the titles in August 1982 when Anderson left Jim Crockett Promotions.[41][42] Anderson and Hansen briefly continued to compete as a tag team in Georgia Championship Wrestling until separating in November 1982.[40] The Wrestling Observer Newsletter named Anderson and Hansen its “Tag Team of the Year” for 1982.[43]

In November 1982, Anderson formed a new tag team with Buzz Sawyer, with the duo facing Tommy Rich and various partners, including Butch Reed, Dick Murdoch, and the Masked Superstar, in a series of matches. Anderson and Sawyer ceased teaming regularly in March 1983.[44] In June 1983, Anderson began feuding with Paul Ellering and the Road Warriors.[45]

In August 1983 at the 35th National Wrestling Alliance convention in Las Vegas, Nevada, Anderson expressed his ire at World Wrestling Federation (WWF) promoter Vince McMahon‘s national expansion in defiance of NWA territorial boundaries, threatening to retaliate by running opposite to McMahon in the WWF’s territory of Pennsylvania.[46]

In 1984, Anderson feuded with his future tag team partner Arn Anderson.[47] Anderson wrestled his final match with Georgia Championship Wrestling in July 1984, teaming with Ronnie Garvin to defeat the Road Warriors in the Macon Coliseum.[48]

Championship Wrestling from Georgia (1984–1985)[edit | edit source]

In July 1984, Jack Brisco, Jerry Brisco, and other shareholders sold their shares in Georgia Championship Wrestling to Vince McMahon for $900,000 (equivalent to $2,639,000 in 2023) in what became known in the wrestling industry as “Black Saturday“. The deal gave McMahon a 90% stake in the promotion and control over Georgia Championship Wrestling’s 6:05 PM ET Saturday night timeslot on TBS, in which World Championship Wrestling had aired since June 1981.[32][49][50][51][52] The sole holdout was Anderson – the head booker of the promotion, and a 10% minority shareholder – who rejected McMahon’s new direction for the promotion and acrimoniously resigned.[49][53][52]

Anderson joined forces with long-time NWA-sanctioned promoters Fred Ward and Ralph Freed to start a new company called Championship Wrestling from Georgia.[17] TBS president Ted Turner granted Championship Wrestling from Georgia a 7:30 AM ET Saturday morning timeslot on TBS, which outperformed McMahon’s revamped World Championship Wrestling in television ratings.[49][50] Championship Wrestling from Georgia promoted its first event in August 1984 and its final event in April 1985,[54] when Anderson sold it to Jim Crockett Jr..[49]

In addition to promoting and booking Championship Wrestling from Georgia, Anderson also wrestled for the promotion throughout its existence. In his first match, in August 1984, Anderson teamed with Brad Armstrong to defeat Bob Roop and The Spoiler in the Macon Coliseum. Anderson went on to feud with Roop, facing him in a series of street fights, cage matches, and taped fist matches. In October 1984 at Championship Wrestling from Georgia’s “Night of Champions” event, Anderson and Dusty Rhodes wrestled AWA World Tag Team Champions the Road Warriors to a double disqualification. In November 1984, Anderson began teaming with Thunderbolt Patterson, with the duo defeating the Long Riders for the NWA National Tag Team Championship in January 1985; they vacated the titles in March 1985 when Anderson turned on Patterson and reformed the Minnesota Wrecking Crew with Gene Anderson; the Minnesota Wrecking Crew teamed together until the promotion’s final event in April 1985.[55][56]

Jim Crockett Promotions and World Championship Wrestling (1985–1994)[edit | edit source]

Minnesota Wrecking Crew; Four Horsemen (1985–1987)[edit | edit source]

Anderson (left) as a member of the Four Horsemen, c. 1987In April 1985, Jim Crockett Promotions acquired Championship Wrestling from Georgia. In the same month, Gene Anderson retired from professional wrestling. Ole Anderson began teaming with Arn Anderson (the real-life Marty Lunde, who facially resembled Ole, and was variously billed as being Ole’s brother, cousin, or nephew),[6][4] as a new iteration of the Minnesota Wrecking Crew.[18][57][58] Later that month, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew defeated Manny Fernandez and Thunderbolt Patterson to win the NWA National Tag Team Championship.[18]

Anderson (left) as a member of the Four Horsemen, c. 1987In April 1985, Jim Crockett Promotions acquired Championship Wrestling from Georgia. In the same month, Gene Anderson retired from professional wrestling. Ole Anderson began teaming with Arn Anderson (the real-life Marty Lunde, who facially resembled Ole, and was variously billed as being Ole’s brother, cousin, or nephew),[6][4] as a new iteration of the Minnesota Wrecking Crew.[18][57][58] Later that month, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew defeated Manny Fernandez and Thunderbolt Patterson to win the NWA National Tag Team Championship.[18]

In September 1985, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew joined Ric Flair in an attack on Dusty Rhodes. The three men, along with Tully Blanchard and his manager J. J. Dillon, went on to form a stable. The following month, Arn Anderson delivered a promo in which he stated that “not since the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse have so few wreaked so much havoc on so many”, leading announcer Tony Schiavone to dub them “the Four Horsemen“. The Four Horsemen swiftly went on to become a dominant heel faction in Jim Crockett Promotions.[57][58][59]

Over the following months, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew successfully defended their NWA National Tag Team Championship against challengers such as America’s Team (Dusty Rhodes and Magnum TA); Brad Armstrong and Steve Armstrong; Ron Garvin and Terry Taylor; and Jimmy Valiant and Sam Houston. At Starrcade ’85: The Gathering that November, they successfully defended the titles against Billy Jack Haynes and Wahoo McDaniel.[18][56] In the main event of Starrcade ’85 between Flair and Dusty Rhodes, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew interfered in an attempt to help Flair retain his NWA World Heavyweight Championship.[60] They held the titles until January 1986, when Ole was injured in a six-man tag team match against Dusty Rhodes and the Road Warriors, forcing them to vacate the Championship.[18][56]

After recuperating from his injury, in March-April 1986, Anderson wrestled in Japan with All Japan Pro Wrestling as part of its Champion Carnival tour. He took part in a tournament for the NWA United National Championship, defeating Killer Khan, losing to Genichiro Tenryu, and wrestling Ashura Hara to a draw; the tournament was ultimately won by Tenryu. Anderson’s other opponents during the tour included Animal Hamaguchi, Haru Sonoda, Rocky Hata, and Takashi Ishikawa.[18]

Following his return from Japan, Anderson resumed teaming with Arn Anderson in Jim Crockett Promotions. In July 1986, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew began a long-running series of matches against the Rock ‘n’ Roll Express. In November 1986 at Starrcade ’86: Night of the Skywalkers, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew unsuccessfully challenged the Rock ‘n’ Roll Express for the NWA World Tag Team Championship (Mid-Atlantic version) in a steel cage match in the Greensboro Coliseum. They continued to team together until February 1987.[18][61]

Feud with the Four Horsemen; tag team with Lex Luger (1987–1988)[edit | edit source]

In February 1987, Anderson left the Four Horsemen after punching Tully Blanchard when he referred to Ole’s son Bryant as a “snot nosed kid”.[62] He subsequently began feuding with the remaining Four Horsemen, facing Blanchard, Arn Anderson, and Dillon in a series of matches. Anderson also vied with Big Bubba Rogers and his manager Jim Cornette, who Dillon had hired to get rid of Ole. In March 1987, he formed a short-lived tag team with Tim Horner. Anderson went temporarily into retirement in July 1987.[18][62]

Anderson returned to the ring in January 1988, forming a tag team with Lex Luger, who had left the Four Horsemen the month prior. Anderson and Luger began feuding with their former stablemates, repeatedly challenging Arn Anderson and Tully Blanchard for the NWA World Tag Team Championship (Mid-Atlantic version). They also joined forces with Dusty Rhodes to face Anderson, Blanchard, and Ric Flair in a series of six-man tag team matches. The tag team disbanded in March 1988 when Anderson returned to retirement.[18]

Four Horsemen reunion (1989–1990)[edit | edit source]

Anderson came out of retirement once more in November 1989, reforming the Minnesota Wrecking Crew with Arn Anderson, who had returned to Jim Crockett Promotions (since renamed “World Championship Wrestling“) after a stint in the World Wrestling Federation. The following month, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew reformed the Four Horsemen – this time as a face stable – with Ric Flair and Sting.[57][59][63] The Minnesota Wrecking Crew went on to compete in WCW’s tag team division, facing teams such as the State Patrol (Lt. James Earl Wright and Sgt. Buddy Lee Parker), the Fabulous Freebirds, the New Zealand Militia (Jack Victory and Rip Morgan), and the Samoan SWAT Team. The reformed Four Horsemen also feuded with the J-Tex Corporation/Gary Hart International, culminating in a steel cage match at Clash of the Champions X: Texas Shootout in February 1990 where the Minnesota Wrecking Crew and Flair defeated Buzz Sawyer, the Dragon Master, and the Great Muta.[18] At the same event, Sting was ejected from the Four Horsemen and the stable turned heel.[59]

At WrestleWar ’90: Wild Thing in February 1990, the Minnesota Wrecking Crew unsuccessfully challenged the Steiner Brothers for the WCW World Tag Team Championship. They challenged the Steiner Brothers on multiple occasions in early 1990, including facing them in a stretcher match, but failed to win the titles.[18] In March-April 1990, Anderson briefly managed two masked wrestlers (Mike Enos and Wayne Bloom) dubbed the Minnesota Wrecking Crew II.[64] Anderson wrestled the final match of his career on April 28, 1990, teaming with Arn Anderson in a loss to Rick Steiner and Road Warrior Animal.[18] He subsequently retired again to manage the Four Horsemen.[57][63]

Retirement; backstage roles (1990–1994)[edit | edit source]

In spring 1990, Anderson began heading the booking committee for WCW, replacing Ric Flair.[9][65] Anderson’s tenure saw some of the more outlandish creative ideas tried by WCW. Among his creations were The Black Scorpion, which was intended to be a nemesis from Sting’s past.[66] After several miscues, the Scorpion’s identity was eventually revealed as Ric Flair, in a ploy to confuse Sting and force him to lose the WCW World Heavyweight Championship back to Flair.[66] The May 1990 pay-per-view Capital Combat saw the fictional character RoboCop come to the ring to rescue Sting.[9] Anderson was dismissed as booker at the end of 1990.[67]

On the June 13, 1992 episode of WCW Saturday Night, Anderson was appointed senior referee of WCW by Bill Watts.[68]

After Bill Watts was ousted as Executive Vice President of WCW in February 1993 and replaced by Bob Dhue, Anderson once again became booker for WCW.[69][70] When Ric Flair returned to WCW that spring, Anderson questioned what value he had after having lost a loser leaves town match to Mr. Perfect on national television in the World Wrestling Federation, which Flair took as a personal attack, leading to him ending their friendship.[71]

In May 1993 at Slamboree, Anderson, Arn Anderson, Ric Flair and Paul Roma appeared on an edition of Flair’s interview segment A Flair for the Gold and declared themselves to be a new line-up of the Four Horseman. Ole Anderson did not reappear following Slamboree and the stable proceeded as a trio.[57]

In early 1994, Eric Bischoff was promoted to replace Bob Dhue; after a series of creative disagreements, Bischoff reassigned Anderson to be head trainer of the WCW Power Plant training school.[5][70][72] in May 1994, at Slamboree, Anderson was inducted into the WCW Hall of Fame.[73] Anderson was fired from WCW by Bischoff in September 1994 after meeting Smoky Mountain Wrestling (SMW) promoter and booker Jim Cornette – who was on bad terms with Bischoff – in the parking lot of the Power Plant to cut promos for his son Bryant’s upcoming debut in SMW.[72]

Legacy[edit | edit source]

After leaving WCW, Anderson retired from professional wrestling. In 2003, he co-authored an autobiography with Scott Teal, titled Inside Out: How Corporate America Destroyed Professional Wrestling.[74][31] In 2010, he was inducted into the NWA Hall of Fame as part of the Minnesota Wrecking Crew.[75]

Fellow professional wrestler Ric Flair described Anderson as “the consummate wrestler – he was tough, he could talk, he looked good in the ring, and he really knew how to wrestle”.[30] The Minnesota Wrecking Crew were one of the highest earning acts in professional wrestling in the 1970s.[6] George Schire described the Minnesota Wrecking Crew as having “reigned as the top tag team in the South for over a decade”.[15] Journalist Alex Marvez described Anderson as “one of wrestling’s top villains in the 1970s and ’80s”; he was stabbed on seven occasions.[76] Writing in 2024, journalists Oliver Lee Bateman and Ian Douglass described Anderson as “one of the best workers and wrestling minds of the previous era”.[6] In 2004, journalist Mike Mooneyham described him as “an intriguing, almost mythical, figure in the wrestling business”.[77]

During Anderson’s stint as booker of Georgia Championship Wrestling, the promotion became highly profitable.[6] His later runs as WCW booker in 1990 and 1993-1994 drew some criticism. Mick Foley, who described Anderson as a “wrestling traditionalist”, resigned from WCW in 1990 after a discussion with Anderson in which he critiqued Foley’s style.[65] Robbie V left WCW in May 1993 shortly after Anderson replaced Bill Watts as booker, feeling he was “lost in the shuffle”.[78] Eric Bischoff described Anderson’s ideas as “dated and unsophisticated”, while praising his “‘feel’ and understanding of the basics of the physical side of storytelling”.[70]

Anderson had acrimonious relationships with many wrestlers.[71] He was characterized by some co-workers as a bully.[79] He criticized former partner and friend Ric Flair for wrestling formulaic matches.[6][31][71] Anderson also criticized, or had disputes with, many other wrestling personalities including Randy Savage,[74] Ernie Ladd,[6] Thunderbolt Patterson,[6] Lex Luger,[80] Eric Bischoff,[80] Tully Blanchard,[80] and Roddy Piper.[80]

From the early 1970s to the early 1990s, Anderson trained several professional wrestlers, among them Don Kernodle; Italian Stallion; Jeff Farmer; Ken Timbs; Mo; and his son Bryant.[81]

Professional wrestling style and persona[edit | edit source]

Anderson was known for his “hard-nosed style and gruff demeanor”.[82] As a member of the Minnesota Wrecking Crew, he wrestled in a stiff, “nothing flashy, no gimmicks” style.[4] Professional wrestling historian Tim Hornbaker described the Minnesota Wrecking Crew as “old-school rough and tumble brawlers with mat knowledge and superior ring psychology”.[7] His signature moves included a diving knee drop,[2] a hammerlock,[2] and an armbar.[83] He was nicknamed “Brute” [15] and “the Rock”.[14][84] He generally wrestled in red trunks, sometimes adorned with yellow stars.[61]

Personal life and death[edit | edit source]

Rogowski had seven children from a marriage that ended in divorce, including Bryant Rogowski, who wrestled as Bryant Anderson. At the time of his death, he had been in a relationship with Marsha Cain for 22 years.[1][77]

In addition to his professional wrestling career, Rogowski at one stage in his life owned a sawmill in Wisconsin.[77]

In July 2007, Gerweck.net reported that Rogowski had multiple sclerosis and had gotten worse with decreased mobility and memory loss.[citation needed] On February 27, 2011, it was announced that Rogowski had been nursing broken ribs due to a fall he had earlier that day, as well as a broken arm.[85]

Rogowski died on February 26, 2024, at the age of 81.[1][82][86]

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

In wrestling

- Finishing moves

- Signature moves

- Managers

- Wrestlers managed

Championships and accomplishments[edit | edit source]

Ole Anderson as tag team champion, c. 1982

Ole Anderson as tag team champion, c. 1982

- American Wrestling Association

- AWA Midwest Heavyweight Championship (2 times)[87]

- AWA Midwest Tag Team Championship (2 times) – with Ox Baker (1 time) and The Claw (1 time)[88]

- Championship Wrestling from Florida

- Championship Wrestling from Georgia

- Georgia Championship Wrestling

- Columbus Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[37]

- NWA Georgia Tag Team Championship (16 times) – with Gene Anderson (7 times), Ivan Koloff (4 times), Lars Anderson (2 times), Jacques Goulet (1 time), Ernie Ladd (1 time), and Jerry Brisco (1 time)[34]

- NWA Georgia Television Championship (2 times)[35]

- NWA Macon Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[33]

- NWA Macon Tag Team Championship (1 time) – with Gene Anderson[91]

- NWA Southeastern Tag Team Championship (Georgia version) (1 time) – with Gene Anderson[29]

- Jim Crockett Promotions and World Championship Wrestling

- NWA Eastern States Heavyweight Championship (1 time)[27]

- NWA National Tag Team Championship (1 time) – with Arn Anderson

- NWA Mid-Atlantic Tag Team Championship (3 times) – with Gene Anderson[92]

- NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Championship (4 times) – with Gene Anderson[25]

- NWA Southern Tag Team Championship (Mid-Atlantic version) – with Gene Anderson (1 time)

- NWA World Tag Team Championship (Mid-Atlantic version) (8 times, inaugural) – with Gene Anderson (7 times), and Stan Hansen (1 time)[41]

- WCW Hall of Fame (Class of 1994)[93]

- National Wrestling Alliance

- NWA Hall of Fame (class of 2010) as part of the Minnesota Wrecking Crew[75]

- Pro Wrestling Illustrated

- PWI Tag Team of the Year (1975, 1977) – with Gene Anderson

- PWI ranked him #74 of the top 500 singles wrestlers of the “PWI Years” in 2003[94]

- Southeastern Championship Wrestling

- Wrestling Observer Newsletter

- Tag Team of the Year (1982) with Stan Hansen[43]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Obituary for Mr. Alan Robert Rogowski”. CarterFHWinder.com. February 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Lentz III, Harris M. (2010). Biographical Dictionary of Professional Wrestling (2 ed.). McFarland and Company. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-4766-0505-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Oliver, Greg (February 26, 2024). “Ole Anderson dead at 81”. SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Mooneyham, Mike (January 18, 2004). “Ole Anderson part 2”. MikeMooneyham.com. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Bateman, Oliver Lee; Douglass, Ian (February 29, 2024). “Ole Anderson was the ghost of wrestling’s past”. TheRinger.com. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Hornbaker, Tim (2023). The Last Real World Champion: The Legacy of ‘Nature Boy’ Ric Flair. ECW Press. p. 34-44. ISBN 978-0-613-33590-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Minnesota State High School League (1957). Minnesota State High School League Bulletin. Vol. 32. p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Truitt, Brandon (January 5, 2004). “Ole Anderson shoot interview”. TheSmartMarks.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Kovachis, Chris (July 27, 2004). “On the road with Ole Anderson”. SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Bayless, Brian (January 6, 2017). “RF Video shoot interview with Ole Anderson”. BlogOfDoom.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – American Wrestling Association”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ “Inside Out by Ole Anderson”. CrowbarPress.com. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stone, David. “Ole Anderson”. KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schire, George (2010). Minnesota’s Golden Age of Wrestling: From Verne Gagne to the Road Warriors. Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8735-1620-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2006). Wrestling Title Histories (4th ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Oliver, Greg; Johnson, Steve (2005). “Top 20: #6 The Minnesota Wrecking Crew”. The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Tag Teams. ECW Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-1-5502-2683-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – Jim Crockett Promotions”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ Bourne, Dick (August 10, 2016). “Meet our baby brother: Ole Anderson”. MidAtlanticGateway.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – Japan Wrestling Association”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2000). “Nebraska: AWA Midwest Tag Team Title [Dusek]”. Wrestling title histories: professional wrestling champions around the world from the 19th century to the present. Pennsylvania: Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2006). Wrestling Title Histories (4 ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ Duncan, Royal; Will, Gary (2006). Wrestling Title Histories (4 ed.). Archeus Communications. ISBN 0-9698161-5-4.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – Championship Wrestling from Florida”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c NWA Atlantic Coast Tag Team Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Stone, David. “Ole Anderson page 2”. KayfabeMemories.com. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b NWA Eastern States Heavyweight Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – International Wrestling Enterprise”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b NWA Southeastern Tag Team Title (Georgia) history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b Flair, Ric; Greenberg, Keith Elliot (2010). Ric Flair: To Be the Man. World Wrestling Entertainment. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4391-2174-0.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bedard, Derek (December 28, 2003). “Wrestling Observer Live radio report with Ole Anderson”. WrestlingObserver.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Watts, Bill; Williams, Scott (2006). The Cowboy and the Cross: The Bill Watts Story. ECW Press. pp. 115, 181. ISBN 978-1-5502-2708-6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b NWA Macon Heavyweight Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e NWA Georgia Tag Team Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b c NWA Georgia Television Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Matches – Ivan Koloff & Ole Anderson”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b NWA Columbus Heavyweight Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – 1979”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ Rickard, Mike (2010). “I Never Was Your Friend, Gordon Solie”. Wrestling’s Greatest Moments. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-5549-0331-3.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Matches – Stan Hansen & Ole Anderson”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b NWA World Tag Team Title (Mid-Atlantic/WCW) history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Bourne, Dick (June 17, 2018). “The sad final chapter in the 1982 World Tag Team Tournament”. MidAtlanticGateway.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Tag Team of the Year”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Matches – Buzz Sawyer & Ole Anderson”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – 1983”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Hart, Bret (2007). Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling. Ebury Press. pp. 142–144. ISBN 978-0-0919-3286-2.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – 1984”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – Georgia Championship Wrestling”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Eddie Mac (July 14, 2017). “This day in wrestling history (July 14): Black Saturday”. CagesideSeats.com. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Molinaro, John F. (July 15, 2012). “End of an era on TBS: Solie, Georgia and ‘Black Saturday'”. Canoe.ca. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Weldon T.; Wilson, Jim (2003). Chokehold: Pro Wrestling’s Real Mayhem Outside the Ring. Xlibris US. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-4628-1172-4.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Phillips, Jim (March 10, 2023). “Georgia Championship Wrestling”. ProWrestlingStories.com. Retrieved March 22, 2024.

- ^ Lambert, Jeremy (September 20, 2022). “Tony Schiavone says Ole Anderson regretted how he treated Vince and Linda McMahon”. Fightful.com. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Championship Wrestling from Georgia – events”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – matches – Championship Wrestling from Georgia”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved February 28, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d NWA National Tag Team Title history Archived 2007-12-18 at the Wayback Machine At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Bourne, Dick (2017). Four Horsemen: A Timeline History. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1545468548.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cawthon, Graham (2013). the History of Professional Wrestling Vol 3: Jim Crockett and the NWA World Title 1983-1989. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1494803476.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Lealos, Shawn S. (October 16, 2023). “Every version of the Four Horsemen, ranked from worst to best”. TheSportster.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Bourne, Dick (November 18, 2015). “The earliest origins of the Four Horsemen”. MidAtlanticGateway.com. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Keith, Scott (November 26, 2020). “The SmarK Rant for NWA Starrcade 86”. BlogOfDoom.com. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “JCP – 1987 results”. TheHistoryOfWWE.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cawthon, Graham (2014). the History of Professional Wrestling Vol 4: World Championship Wrestling 1989-1994. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1499656343.

- ^ Labbe, Michael J. (September 29, 2020). “Same tag team different gimmick”. TheWrestlingInsomniac.com. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Foley, Mick (2000). Have a Nice Day! a Tale of Blood and Sweatsocks. Turtleback. p. 235-236. ISBN 978-0-613-33590-4. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b RD Reynolds; Randy Baer (2003). Wrestlecrap – the very worst of pro wrestling. ECW Press. ISBN 1-55022-584-7.

- ^ Oliver, Greg (December 22, 2003). “Ole lets lose in new book”. SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Colling, Bob (December 13, 2013). “WCW Saturday Night 6/13/1992”. WrestlingRecaps.com. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Keith, Scott (May 19, 2017). “Wrestling Observer Flashback–02.22.93”. BlogOfDoom.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bischoff, Eric; Roberts, Jeremy (2006). Controversy Creates Cash. Simon and Schuster. pp. 83, 102–106. ISBN 978-1-4165-2729-9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Chin, Michael (March 2024). “Ole Anderson: why he was one of the most hated men in wrestling history”. TheSportster.com. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Keith, Scott (May 21, 2018). “Wrestling Observer Flashback–09.26.94”. BlogOfDoom.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ “WCW Slamboree: history 1994”. WCW.com. World Championship Wrestling. Archived from the original on May 11, 2000.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Oliver, Greg (January 5, 2004). “Ole Anderson offers insights and insults”. SlamWrestling.net. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Boone, Matt (December 20, 2010). “2010 class of the NWA Wrestling Hall of Fame revealed”. WrestleZone.com. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- ^ Marvez, Alex (May 14, 2004). “Legendary villain has a grudge and he isn’t faking it”. Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mooneyham, Mike (January 11, 2004). “Ole Anderson part 1”. MikeMooneyham.com. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Fisher, Kieran (November 27, 2023). “RVD details issues working under Bill Watts and Ole Anderson in WCW”. WrestlingInc.com. Retrieved March 7, 2024.

- ^ Riesman, Abraham Josephine (2023). “Get Over, Act I”. Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America. Atria Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-9821-6944-2.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Mooneyham, Mike (January 17, 2004). “Ole Anderson speaks out”. MikeMooneyham.com. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Kreikenbohm, Philip. “Ole Anderson – entourage”. Cagematch.net. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Ole Anderson passes away”. WWE.com. WWE. February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Saalbach, Axel. “Ole Anderson”. WrestlingData.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Bourne, Dick (May 16, 2021). “How firm a foundation: what Ole Anderson left to Arn Anderson and the Four Horsemen”. MidAtlanticGateway.com. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ “Ole Anderson Suffers Nasty Injury”. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Rose, Bryan (February 26, 2024). “Four Horsemen member Ole Anderson passes away at 81 years old”. Wrestling Observer – Figure Four Online. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ AWA Midwest Heavyweight Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ AWA Midwest Tag Team Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ NWA Florida Television Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ NWA Florida Tag Team Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ NWA Macon Tag Team Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ NWA Mid-Atlantic Tag Team Title history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ WCW Hall of Fame history At wrestling-titles.com

- ^ “Pro Wrestling Illustrated’s Top 500 Wrestlers of the PWI Years”. Wrestling Information Archive. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ NWA Southeastern Heavyweight Title history At wrestling-titles.com

External links[edit | edit source]

- Ole Anderson’s profile at Cagematch.net

, Wrestlingdata.com

, Wrestlingdata.com  , Internet Wrestling Database

, Internet Wrestling Database

- Alan Rogowski at IMDb

- 1942 births

- 2024 deaths

- 20th-century male professional wrestlers

- American male professional wrestlers

- American people of Polish descent

- Anderson family

- Deceased American professional wrestlers

- Military personnel from Minneapolis

- Military personnel from Minnesota

- NWA Florida Tag Team Champions

- NWA Florida Television Champions

- NWA Georgia Tag Team Champions

- NWA Macon Heavyweight Champions

- NWA Macon Tag Team Champions

- NWA National Tag Team Champions

- NWA National Television Champions

- People with multiple sclerosis

- Professional wrestlers from Minneapolis

- Professional wrestling managers and valets

- Professional wrestling promoters

- Professional wrestling referees

- Professional wrestling trainers

- The Four Horsemen (professional wrestling) members

- WCW World Tag Team Champions

- World Championship Wrestling executives