The Police Misconduct Caught on Tape Before Rodney King

When Rodney King died in 2012—almost exactly two decades after his 1992 beating became the most famous example of police brutality caught on video—the writer Touré noted in TIME that what happened at the hands of Los Angeles cops did not make King special. “What separated [the incident] from others was that 81 seconds of it was surreptitiously videotaped by a stranger, giving the world a look at the police coldly and cruelly beating a black man,” he wrote

That difference, the infamous tape, has placed Rodney King at the start of a continuum that stretches ever on, as citizen-filmed footage and police-worn body cameras and dash-cams reshape our understanding of the relationship between law enforcement and the public they’re sworn to protect. The camcorder footage of King’s savage beating did mark a critical moment in America’s long and tangled racial history, but it was not the first incident of police misconduct to be caught on camera.

Home movies had been around for decades by the time King had his run-in with the police, and Americans had gotten used to filming all kinds of moments from daily life. In the early years, however, those cameras were clunky, only able to capture short, soundless clips. That changed by the late 1970s with the advent of video tape recorders and then easy-to-use 8-mm camcorders. By 1991, plenty of people had and used video cameras. While most used them to chronicle birthday parties and days at the beach, they were also used to capture some galling examples of police misconduct. When the news of King’s beating broke, TIME rounded up just a few examples of “America’s ugliest home videos,” including:

Those four examples, however, would prove to be only half parallel with the King case. Despite the video footage, which had been captured by a man named George Holliday, a criminal jury did not find the four officers who were tried in the case to be guilty. The footage did, however, help puncture the idea that such events almost never occurred, as one TIME reader wrote in a letter in April of 1991. “How could the beating of Rodney King be an isolated event?” asked Rob Adelman of Westminster, Calif. “The odds against capturing it on videotape are enormous unless such occurrences are more common than we thought. And why did nobody ever hear racist communications between police officers before? Could it be that someone was listening and didn’t care?”

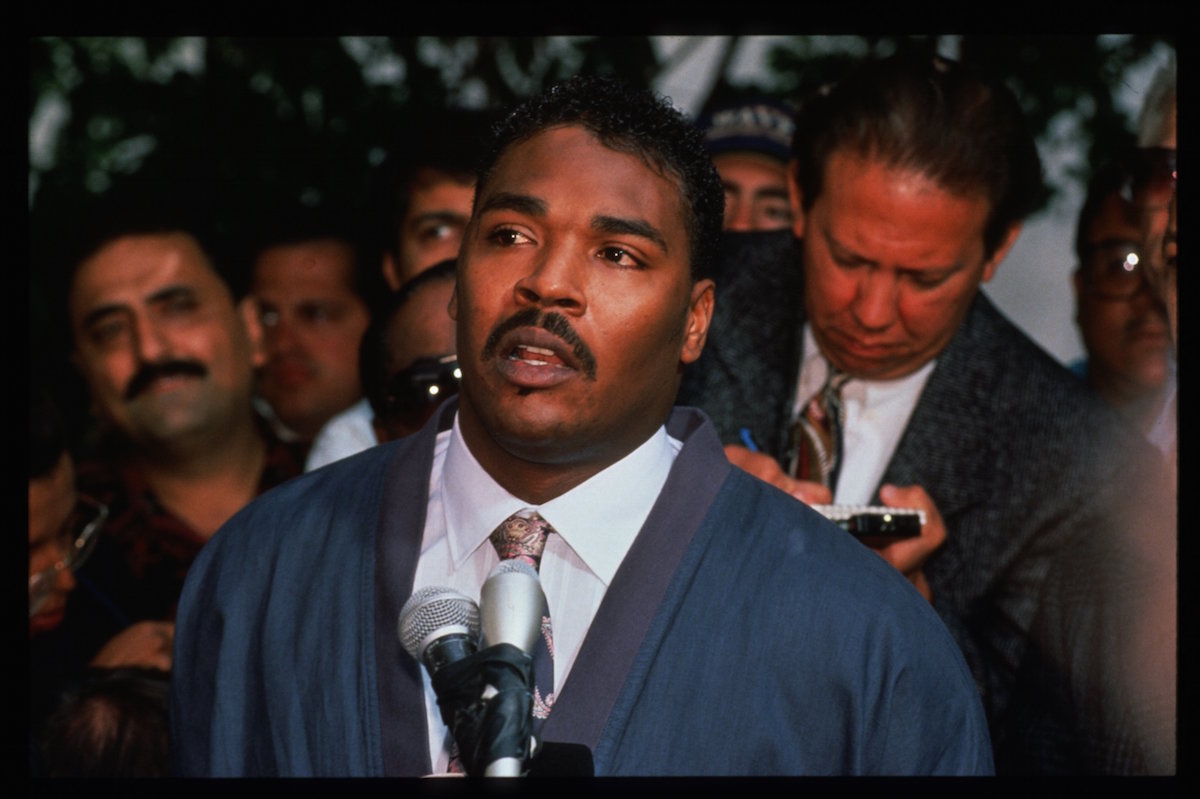

At 12:45 a.m. on March 3, 1991, robbery parolee Rodney G. King stops his car after leading police on a nearly 8-mile pursuit through the streets of Los Angeles, California. The chase began after King, who was intoxicated, was caught speeding on a freeway by a California Highway Patrol cruiser but refused to pull over. Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) cruisers and a police helicopter joined the pursuit, and when King was finally stopped by Hansen Dam Park, several police cars descended on his white Hyundai.

A group of LAPD officers led by Sergeant Stacey Koon ordered King and the other two occupants of the car to exit the vehicle and lie flat on the ground. King’s two friends complied, but King himself was slower to respond, getting on his hands and knees rather than lying flat. Officers Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, Ted Briseno, and Roland Solano tried to force King down, but he resisted, and the officers stepped back and shot King twice with an electric stun gun known as a Taser, which fires darts carrying a charge of 50,000 volts.

At this moment, civilian George Holliday, standing on a balcony in an apartment complex across the street, focused the lens of his new video camera on the commotion unfolding by Hansen Dam Park. In the first few seconds of what would become a very famous 89-second video, King is seen rising after the Taser shots and running in the direction of Officer Powell. The officers alleged that King was charging Powell, while King himself later claimed that an officer told him, “We’re going to kill you, n*****. Run!” and he tried to flee. All the arresting officers were white, along with all but one of the other two dozen or so law enforcement officers present at the scene. With the roar of a helicopter above, very few commands or remarks are audible in the video.

With King running in his direction, Powell swung his baton, hitting him on the side of the head and knocking him to the ground. This action was captured by the video, but the next 10 seconds were blurry as Holliday shifted the camera. From the 18- to 30-second mark in the video, King attempted to rise, and Powell and Wind attacked him with a torrent of baton blows that prevented him from doing so. From the 35- to 51-second mark, Powell administered repeated baton blows to King’s lower body. At 55 seconds, Powell struck King on the chest, and King rolled over and lay prone. At that point, the officers stepped back and observed King for about 10 seconds. Powell began to reach for his handcuffs.

At 65 seconds on the video, Officer Briseno stepped roughly on King’s upper back or neck, and King’s body writhed in response. Two seconds later, Powell and Wind again began to strike King with a series of baton blows, and Wind kicked him in the neck six times until 86 seconds into the video. At about 89 seconds, King put his hands behind his back and was handcuffed.

Sergeant Koon never made an effort to stop the beating, and only one of the many officers present briefly intervened, raising his left arm in front of a baton-swinging colleague in the opening moments of the videotape, to no discernible effect. An ambulance was called, and King was taken to the hospital. Struck as many as 56 times with the batons, he suffered a fractured leg, multiple facial fractures, and numerous bruises and contusions. Unaware that the arrest was videotaped, the officers downplayed the level of violence used to arrest King and filed official reports in which they claimed he suffered only cuts and bruises “of a minor nature.”